Fugit inreparabile tempus - the time for change is now!

Written by Matthew Salik, Head of Programmes, CPA Headquarters Secretariat

Article posted on 07/12/2023

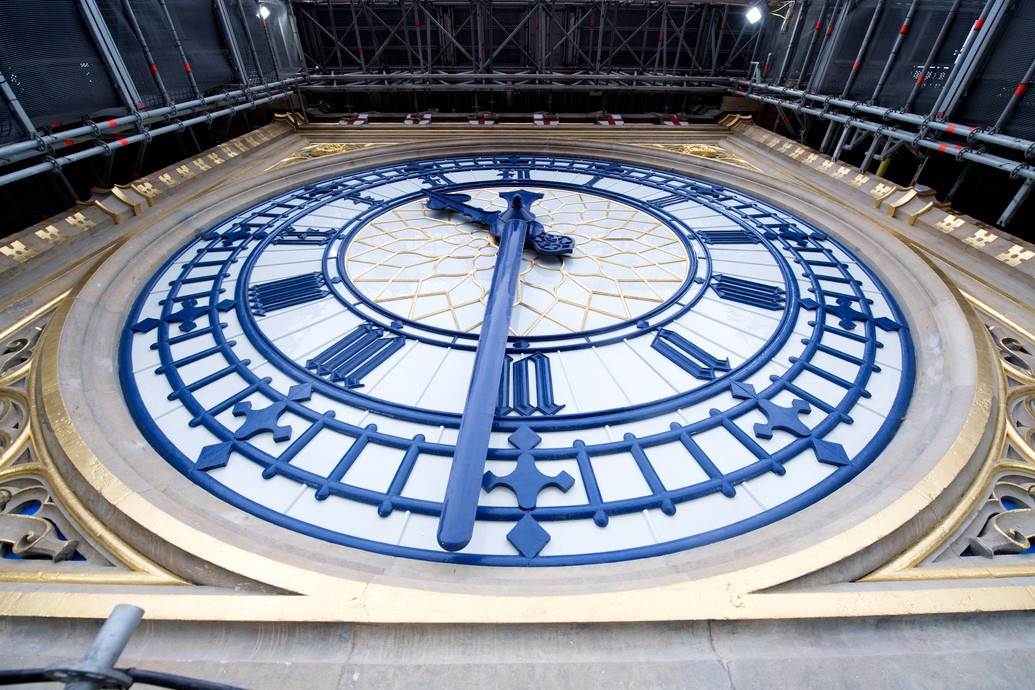

Following on from the brilliantly horologically-oriented article on parliamentary clock towers, I got to thinking a lot about the nature of time and the workings of Parliament. It’s easy to pass by the Elizabeth Tower near the CPA Headquarters Office in London and gaze in wonder at the sheer scale of the great clock tower, more commonly known as Big Ben.

To think, back in the day people used to set their watch by it. Which might give the impression that the UK Parliament has a certain mastery of time [insert joke on Dr Who Time Lords!]. But as this article seeks to highlight, it’s the UK Parliament’s neighbours in Whitehall that have a firm grip on the swinging pendulum. How this problem is replicated across the Commonwealth is something which needs to be examined. I think that time has come.

Often, my time at the CPA is taken up with helping Parliaments strengthen their autonomy and powers in line with the Commonwealth Latimer House Principles on the Separation of Powers[1] (also see Part 1 of this Blog Series), appropriate when you consider the CPA was instrumental in its creation.

In 2023, the CPA is celebrating the 20th anniversary since the Principles were formally approved by Commonwealth Heads of Government. My work focuses mainly on the financial and administrative independence of Parliaments. But an important, often overlooked part of the discourse on the Separation of Powers is Parliament’s power over time, or lack thereof. Time is in fact one of the most important resources, and one that is most constrained by governments across the Commonwealth. But what do we mean by Parliamentary time? I have grouped these into four areas.

- Time as a resource – for example, providing enough time for Parliament and its Parliamentarians to fulfil their constitutional mandate (legislate, scrutinise, hold to account, represent, etc).

- Time as a plan – for example, being forewarned as to when Parliament sits, length of parliamentary session, when a Bill is being laid.

- Time as a sacrifice – for example, Parliamentarians’ time being wasted or poorly applied on extraneous things and inefficiencies, which ultimately means sacrificing personal time.

- Time as money – for example, where the highest financial burden for Parliaments are incurred based on the frequency or length of time Parliament sits.

But what does all this actually look like, and what are the implications? Some of these temporal-related challenges are listed below:

Time as a plan and parliamentary sitting calendars: Believe it or not, some Parliaments don’t have a sitting calendar. There can be instances in many Commonwealth Parliaments when determining the dates when Parliamentarians will come together to sit in the Chamber or Committee room is decided on an ad hoc basis. This can be extremely challenging not only for Members and parliamentary staff, but also the public. Ironically for governments, civil servants can also be kept in the dark – which is rather counter-intuitive if the motive behind such an action is to handicap the opposition.

The issue becomes even more contrary from a Separation of Powers perspective when we discover that it is the government’s call to determine when Parliament sits. Of course, it can be the privilege of the government in consultation with wider parliamentary stakeholders to determine sitting dates, recess dates, special events, etc. But for some it is literally the case of the Speaker asking permission of the President whether Parliament can sit, which regrettably may be refused. Fortunately, most Parliaments do have an annual calendar, but disappointingly these calendars are not always publicly available on a website or via a Gazette, and therefore the public’s engagement with Parliament becomes constrained. Time as a plan is ultimately non-existent.

Did you know… the CPA Recommended Benchmarks for Democratic Legislatures, which are the minimum standards applicable to Legislatures, state that:

“2.3.2 – The Legislature shall have procedures for calling itself into regular session. And 2.4.4 – There shall be an annual parliamentary calendar to promote transparency.[2]”

Time as a resource and infrequent sittings: Some Parliaments sit infrequently. Some sit every week, every month, some quarterly. During the COVID-19 pandemic, some barely sat at all over the course of a year. There are of course a range of factors for this. Some jurisdictions have historically sat infrequently, in part due to their size, historical precedence and because some Parliaments place an overreliance of governmental stakeholders to generate sufficient parliamentary business. Other jurisdictions share their parliamentary space with the judiciary and court rooms. It is frequently the case that Parliaments simply don’t have the financial resources to sit as often as they would like.

The infrequency of parliamentary sittings can make it difficult for Parliaments to retain relevancy. In the age of 24-hour media and especially social media and its super-fast pace of discourse and debate, by the time a Parliament decides it will sit and debate an issue, the public have bounced the topic around, consumed a surfeit of ill-informed opinions, fake-news and bigotry and concluded its everybody’s fault, especially legislators who “don’t do anything”. This is of course a rather extreme simplification, but the point is that Parliaments were (in an ancient Greek sense) intended to be the debating centres of society.

If Parliaments do not keep up, then that responsibility will fall to Facebook, Twitter and TikTok. Parliaments of the 21st century must fulfil so many tasks, legislate, debate important issues, force governments to be open, transparent and effective through scrutiny, educate the public, advocate on important issues, speak on behalf of their constituents, champion causes, push for reforms, etc. If all that can be undertaken just one day a month, and at the same time ensure Parliament remains relevant and in touch with the public zeitgeist, then that is an impressive achievement indeed.

Time as a resource and legislative time constraints: What are your thoughts about effective scrutiny when all the stages of a Bill are passed in a single sitting day? Or having the ability to present ‘Private Members’ legislation, but no parliamentary time is allocated to consider it? How about Bills tagged with a range of programming or ‘guillotine’ motions to limit the time it can be debated and amended?[3]

What about sitting until the early hours of the morning trying to time out the upper chamber from debating and amending a Bill? What about not providing time for scrutiny of draft legislation or for that matter post-legislative scrutiny? If you think these are rare and extreme cases of governments attempting to drive through laws by cutting off the time Parliament has to properly legislate, then you’d be mistaken. These tactics are employed across the Commonwealth (and beyond) by governments every day and they are highly effective strategies.

Worryingly, there is a general acceptance of such a status quo as simply the cost of doing business. There are also problems with the fact that because of limited legislative drafting capacity Commonwealth-wide, there isn’t more time available in drafting Bills. This is further compounded by the lack of a comprehensive legislative calendar which lets a Parliament know what Bills will be presented over the course of a year or more. This means background research by libraries can’t always be produced on the Bill, and so a Parliamentarian will have little idea what they are voting on. Ultimately these approaches arguably lead to a failure to produce quality, robust, sustainable and effective legislation.

Time as a sacrifice and the cultural and psychological constraints: Beyond the procedural and administrative time constraints existing in most Commonwealth Parliaments, some of the most damaging consequences of poor use of time impact upon the mental health and wellbeing of Parliamentarians. Imagine having a job requiring you to be on call around 20 hours a day (and it not be a matter of life and death)? What about having to wait around in Parliament late into an evening on the assumption that a decisive vote may take place? How are you able to prioritise family time or personal development if you have to cancel your plans last-minute because Parliament or, more precisely, the government have decided they want to put through some ‘emergency legislation’ and are summoning all Members back to Parliament. How would that affect your mental health, stress levels and how conducive is this to your family or work-life balance?[4]

The answer to that question is demonstrated by the number of Parliamentarians choosing to end their careers early or having their marriages end in divorce[5].

Did you know… that women Parliamentarians can, in many jurisdictions, be more detrimentally impacted by the poor use of parliamentary time. According to CPA’s Gender Sensitising Parliaments Guidelines - Dimension 2 states that:

“There should be certainty over the scheduling of parliamentary business; Parliaments’ sittings reflect ‘core business hours’; parliamentary recesses match school holidays.[6]”

Time as a plan and elections: ‘For whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee’ highlights that for those Parliamentarians who are elected to office, general elections can be the turning of the hourglass in political careers. But who typically has the power to call elections? Governments of course, unless you are a lucky Parliamentarian who is based in a jurisdiction with a fixed parliamentary term. If you have a fixed term, there is more certainty, the ability to plan, to consider what is achievable within a certain timeframe, make promises that could be kept and much more. But if you don’t, then electioneering begins much earlier, which means less time in Parliament. It means Election Commissioners have little time to plan and conduct a more proficient election, and Commonwealth Election Observation Mission reports are littered with such criticisms[7].

The frequency and uncertainty around elections also has a far greater and more insidious problem – short-termism. In other words, the increased likelihood that Members may preoccupy themselves with short-term issues and short-term solutions. Developing policies for the next few months or year rather than considering decades and centuries. Migration, climate change, mortality rates, social welfare policies and emerging technologies can’t be addressed by policies that have a one-year lifespan.

Time as money and Members’ salary: It is frequently the case that Parliaments simply don’t have the financial resources to sit as often as they would like. In some jurisdictions, Members are paid every time they attend Parliament[8].

If finances are constrained this might hinder how often and how long a Parliament can sit. Therefore, time becomes even more precious and when Parliaments do sit in such circumstances, they will be directed to meet the needs of government businesses over that of opposition business.[9]

Placing a Parliament on a more secure and sustainable footing could go some way to overcome this hinderance where it exists.

There are of course countless other examples. If I was to include time in relation to Parliamentary Committees[10], this article may run into several hundred pages.

BUT WHAT CAN BE DONE, IF ANYTHING?

Robust Standing Orders are essential as well as a proactive Presiding Officer and Members who can use them. Standing Orders provide a level playing field to ensure that time is fairly allocated and used to maximum potential by all Members.

Separation of Powers should be enshrined in your constitution. It is really important to ensure that no government can reduce a Parliament to nothing more than a rubber stamp for its policies. Checks and balances are key. If an opposition or opposing view can never be voiced, then those people who share such views will seek alternative routes to have their views heard.

Sitting more frequently will ensure there is naturally more time available for parliamentary business. It will ensure Parliament is more relevant and reactive to issues and challenges that may arise. It will be an institution more readily in the public’s conscious.[11]

Members should not make assumptions around how a Parliament should conduct itself. If it doesn’t seem right and it doesn’t work, try and change it.

Fight for the time. It is important for Members to remember there are people in government and Parliament who are responsible for how time is allocated and for what. These people should be accessible, the work they do and the decisions they make should be held to account.

Be prepared. It is essential that Parliaments, Members, parliamentary staff and especially the public know what is happening in Parliament and when. Planning far in advance is key, and having a sitting calendar and legislative calendars are vital for a Parliament to function effectively.

Virtual Parliaments whereby Parliaments should enable alternative methods for Members to conduct their business. Proxy, remote or absent voting should be considered to give Members more time for business outside of Parliament.

Family friendly Parliaments should also be a key consideration to enable a healthy work-life balance for Members and parliamentary staff. An exhausted, stressed and distracted Parliamentarian cannot effectively serve their constituents, or anyone else for that matter. Sittings in business hours, sufficient recess time, maternity and paternity leave and wider family friendly services like a creche should be key considerations.

Efficiency and time are also key to an effective Parliament. Presiding Officers should ensure that precious time is not wasted or abused. Avoiding the duplication of questions, encouraging concise speeches, ensuring timely reporting from Committees are just some of the things needed to be considered.

TIMES UP!

There are, no doubt, many other approaches which could be taken to solve these weaknesses in Parliament, ranging from training on how Parliaments should work, to giving Parliaments more financial and administrative autonomy.[12] Ultimately, the issue of parliamentary time and its management is a critical aspect that needs to be addressed across the Commonwealth and beyond.

The constraints faced by Parliaments in relation to time have far-reaching implications for their effectiveness, public engagement and the overall functioning of democratic systems. The lack of a reliable sitting calendar, infrequent sittings, legislative time constraints, cultural and psychological pressures, and the impact of elections and opposition dynamics all contribute to the challenge.

However, there are potential solutions to improve the situation. Robust Standing Orders, enshrining the Separation of Powers, increasing the frequency of sittings, advocating for transparency and accountability, embracing e-Parliaments, promoting family-friendly practices, and ensuring efficiency in parliamentary proceedings are all crucial steps that can be taken to address the issue and empower Parliaments to fulfil their constitutional mandates. By valuing and prioritising time, Parliaments can enhance their relevance, responsiveness and impact in serving their constituents and upholding democratic values.

The time for change is now!

The title is Latin for ‘it escapes, irretrievable time’ and is a quote by Virgil, typically abbreviated to Tempus Fugit.

References:

[1] Check out the other blog post on Power of Parliaments Blog Series – Part 1.

[2] CPA Benchmarks for Democratic Legislatures

[3] Ibid - 2.5.2: The Legislature shall provide adequate opportunity for legislators to debate Bills prior to a vote. 7.2.2: The Legislature shall have a reasonable period of time in which to adequately scrutinise and debate the proposed national budget.

[4] CPA Mental Health Toolkit sited from Poulter D, Votruba N, Bakolis I, Debell F, Das-Munshi J, Thornicroft G. Mental health of UK Members of Parliament in the House of Commons: a cross-sectional survey.

[5] Between 2010-2015 within the UK Parliament, 12% of Parliamentarians got a divorce. Most notably of the 6 Members of the Scottish National Party elected in 2010, 66% got a divorce whilst serving. Cited in I. Hardman, 'Why We Get the Wrong Politicians', 2019.

[6] CPA and CWP Gender Sensitising Parliaments Guidelines: Standards and a Checklist for Parliamentary Change

[7] For example, CPA BIMR Election Observation Mission Report, British Virgin Islands 2015, 2019 and 2023

[8] For example, in Malawi or in the UK (House of Lords).

[9] CPA Benchmarks for Democratic Legislatures – 2.4.3: A substantial proportion of the Legislature’s time is set aside for it to consider business proposed by non-Government Members.

[10] CPA Benchmarks for Democratic Legislatures – 3.1.4: Once established, Committees shall meet regularly in a timely and effective manner and 3.1.5: All Committee votes and substantive decisions, and the Committee’s reasons for them, are made public in an accessible and timely manner.

[11] CPA Benchmarks for Democratic Legislatures – 2.3.1: The Legislature shall meet regularly, at intervals sufficient to fulfil its responsibilities.

[12] As recommended in the CPA Model Law for Independent Parliaments: Establishing Parliamentary Service Commissions for Commonwealth Legislatures, 2020

Return to the CPA blog series: 'Commonwealth Latimer House Principles 20 Years On: 'Power of Parliaments'

Follow the CPA on social media to continue the discussion online.